Fashionable Nonsense by physicists Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont is a reminder of the vulnerability of language to absurd confabulations. Immaterial of whether it is read or not, one needs to know that such a compilation exists. It documents an important phenomenon that is prevalent in the nature of language in everyday communication: that Common Language of Communication (LCUs) is a poor tool to formulate arguments based on reason. This suggestion is particularly interesting as it speaks to the central thesis of this blog. In fact, the book documents language as a tool that could be used to confuse and obfuscate.

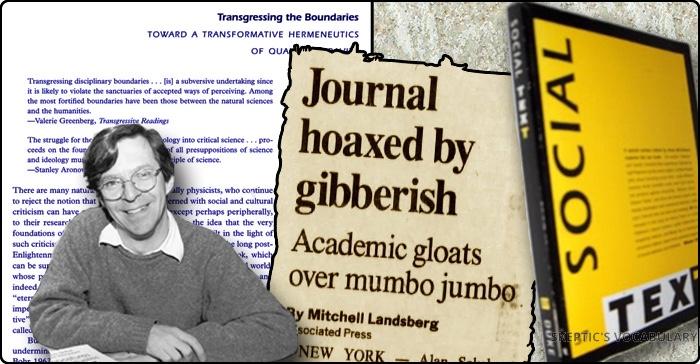

The theme of Fashionable Nonsense emerged from a hoax Alan Sokal played in a humanities journal called Social Text. He constructed an article titled in a grandiose manner –Transgressing the boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity – by interspersing conclusions from quantum physics with quotations from influential postmodern theorists on the relationship between “new physics” and “postmodern thinking”. Sokal was inspired to develop the hoax based on the commentary of science writers Paul Gross and Normal Levitt who stated that new generation humanities journals would publish anything as long as it sounds postmodern.

Postmodernism is a heterogeneous movement in literary theory, sociology, architecture and philosophy that emerged in the second half of the 20th century as a radical departure from the sensibilities of what was considered “modernity and modernism”. Modernity loosely emerged from 17th century European ideas that developed as part of The Enlightenment, which broke away from medieval ideas of the nature of state, government and freedom. It has its origin in the works of European thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Locke, Adam Smith and David Hume. These thinkers upheld social and political doctrines based on reason and delimited the influence of religion on affairs of the State (see for example, Social Contract). They promoted the ideas of liberty, democracy, citizen rights, rationality and the separation of religion and politics. Western scientific revolution and industrialisation closely followed the The Age of Enlightenment. The discovery of oceanic trade routes eventually led to colonialism, which however, triggered a conflict of values and interests with the native population of the new-found continents. True to the pragmatism of the merchant class, the colonisers conducted their trade in ways that suited their medieval instincts: marginalisation of the native population and destruction of their habitat. Back home, many thinkers who preached the Enlightenment values to their population, rationalised the excesses of the colonisers by describing the colonised as inferior in many values common to Christian Europeans. For instance, John Locke, whose views were cardinal to the development of ideas like citizen rights and the limits of State power, and the principal influence on the American Declaration of Independence, justified the subjugation of Native-Americans in the “New World” (Americas).

John Locke wrote, “God gave the World to Men in Common; but … it cannot be supposed he meant it should always remain common and uncultivated. He gave it to the use of the Industrious and Rational, not to the Fancy or Covetousness of the Quarrelsome and Contentious.”

Locke, in effect, justified the removal of Native Americans from their land, stating that they do not have the “rationality” to put those tracts of land to use. Locke’s justification of appropriating the land of Native Americans became the general justification of European colonisation throughout the world(See Manifest Destiny).

“Among the categories of persons denied the benefits and rights that liberalism theoretically promised to all human beings were, variously, indigenous people, the enslaved, women, children, and the mentally disabled, those whom Locke called ‘mad Men’ and ‘Idiots’. The main criterion used to exclude such persons was their lack of rationality, and it has been argued that ‘[t]he American Indian is the example Locke uses to demonstrate a lack of reason’”(Armitage, 2012)

Thus, the ideas of rationality and liberty associated with modernity were also associated with European imperialism, colonialism and atrocities related to the subjugation of native populations. The two world wars were the culmination of the European scramble for global domination and mutual competition. World War II, in many ways, was the climax of this “theater of modernity”. It reached its orgasmic peak with two critical events: the postwar unraveling of the extend of Nazi atrocities, and the destruction that followed the atomic bomb holocaust in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I would date the definitive origin of postmodernism to these two catastrophic events. In both these situations modernity, rationality, science and the instruments of power it created were clearly associated with the catastrophes witnessed. In subsequent years the relationship between modernity and the wanton exercise of its instruments of power was closely interrogated. Postmodernism emerged as the product of the skeptical “revision” of the ideas of modernity. Many postmodern writers found deep fissures and violence in the very narrative of modernity in how it drew different standards for different people. The universalism of the ideas of modernity was questioned, and the dynamics of violence in its structure was examined.

Postmodernist thinkers tried to associate “rationality” and “science” with western imperialism and its devastating consequences. A breed of writers who started to think in the reverse direction started to emerge. Thus, there were thinkers who started to discuss various heterodox relationships: power and knowledge, power and gender, and power and social institutions.

However, in doing so they seemed to have divorced from the clarity of thought that many thinkers of the Enlightenment had. Whether this was a deliberate attempt, or a consequence of the flight of speculations these writers engaged in, is a debatable issue. My impression is that it began as a deliberate attempt (the style of writings of postmodern philosophers like Jacques Derrida, who introduced the literary technique of “deconstruction”), but subsequently the lingo led to many authors getting carried away with their own narrative style.

Concurrent to these developments in the humanities, but unrelated to the stream of thinking in humanities, was a development in the philosophy of science that apparently corroborated the standpoints of the postmodernists. This was a series of ideas that began with Thomas Kuhn, philosopher of science, that made evident the non-rational sociological influences in the way communities of scientists behave in different periods of the history of science. This was in contrast to the “heroic” depictions of staunchly rational science as described by many of Kuhn’s predecessors like Karl Popper and the logical positivists. Drawing extensively from the history of science, Kuhn demonstrated the vagaries of scientists in their endeavour to generate scientific knowledge, in his highly influential book, The Structure of Scientific Revolution. Although Kuhn did not refute the basic validity of science in his writings, his demonstration of its “sociological issues” led to the postmodern interpolation into the nature of science.

Paul Feyerabend, picked up this strand of thought and described an anarchic view of the philosophy of science that refuted its differentiation from other belief systems like myths and religion. These ideas prompted many postmodern authors to argue that science is just one among the numerous other viewpoints of the world, and that it does not command a special status vis-à-vis belief systems of various native communities. Beyond this, there were authors who started to explore a relationship between phenomena described in quantum physics and eastern mysticism. These loose interpretations of the facts of science were aided by opaque language that many a time defied to provide any clarity of understanding. Language was used in an unintelligible manner and connections were made with disconnected and dissimilar entities. I would argue that over a period of time, postmodernism developed a sociological milieu for themselves where “opacity and disconnection” was, as a matter of style, tolerated by a whole community of authors and readers. The style of writing was so well established in the mainstream discourse of postmodern humanities that it required a “child” who did not share the same sociological milieu to call their bluff and shout that the king is naked. Alan Sokal, physicist by training, turned out to be the child who didn’t share the fashion sense of the postmodernists.

Fashionable Nonsense is a sequel to the “Sokal hoax” in the manner in which it exposes postmodern writers for their abuse of language and scientific concepts. It describes a community of people who encourage obfuscation in their communications. Sokal and Bricmont give detailed excerpts of authors who tried to freely interpret concepts in mathematics and physics to form connections in unrelated terrains like literary and cultural studies. The authors discuss in-length, writers like psychoanalyst-feminist Julia Kristeva, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, feminist-psycholinguist-cultural theorist Luce Irigaray, philosopher-anthropologist-sociologist Bruno Latour, sociologist-philosopher-cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard, philosopher-cultural theorist Paul Virilio, philosopher Gilles Deleuze and philosopher-psychotherapist Felix Guattari.

While Sokal and Bricmonts’s critique was limited to the abuse of concepts of science by postmodern writers, the larger issue the authors documented is the issue of intellectual porosity of commonplace language that allows inconsistent and incredulous ideas to populate a variety of scholarly fields in humanities. It demonstrates a certain slackness in exercising rationality in the readers of these fields, while reading texts. As mentioned before, I consider this to be a general problem with language itself. While grammatical errors are immediately detected by readers, logical flaws are seamlessly incorporated in the narratives written in languages of common use. This blog highlights this as a serious issue which perpetuates nonsensical thinking and flawed reasoning in social circles. In more than one way, Fashionable Nonsense is a must-read reference book for those who are concerned about irrationality in public discourse forums.

_______________________________________________________________________

- John Locke, ‘Morality’ Natural Rights Theories: Their Origin and Development. Cambridge, 1979. Quoted by Armitage D. John Locke: Theorist of Empire?. department of History, Harvard University.

- Barbara Arneil, ‘Citizens, Wives, Latent Citizens and Non-Citizens in the Two Treatises: A Legacy of Inclusion, Exclusion and Assimilation’, Eighteenth-Century Thought, 2007.

Hits: 557