(1/6)

World Order, a sweeping tour of the world of high politics and diplomacy, is one of the last publications of the US diplomat and former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger. Kissinger was the secretary of state when two major events in the postwar world happened- the Vietnam war and the US- China détente. While Kissinger’s role in the Vietnam war is much maligned, his role in US China détente make him a revered figure in the US and Chinese diplomatic circles. Kissinger was described as a war criminal for his role in bombing Cambodia by the British journalist Christopher Hitchens, while China decorated him with their highest diplomatic honour, the Friendship Medal of the People’s Republic of China. Paradoxically, Kissinger was awarded the Nobel peace prize for his role in ending the Vietnam war, a prize he was supposed to share with the Vietnam war leader, Le Duc Tho. Tho would refuse the award, while Kissinger would seek to return the prize as an afterthought, apparently after the North Vietnamese forces took over South Vietnam capital Saigon by force. By the range of consequences of his tenure, Kissinger is arguably one of the most influential Secretaries of State in the history of USA.

‘World order’ narrates the story of politics and diplomacy that played out between nations to create an order of global power relationship. Kissinger tries to understand politics of the region through the lens of the historical experience and the world view of the regimes of the region. He takes this journey region by region: From Europe and the West to Russia and Eurasia through China, Persia-Arabia, Japan and India.

The book treats the Western situation exhaustively, while many regions like East Asia, West Asia, India are treated superficially. Africa is not discussed at all. But as the West and the US had influenced the global political order most decisively, it is of importance to listen to Kissinger.

Kissinger, himself the US secretary of state at the time of major global events like the US-Vietnam war and the China-US diplomatic rapprochement, is an insider to the thinking of the superpowers of his time. His doctoral thesis at Harvard, titled ‘Peace, Legitimacy and Equilibrium ( A study of the statesmanship of Castlereagh and Metternich)’ was on power play between European nations in the 19th century.

In this series of articles, we would be following Kissinger through his discussion of how global political order unfolded. We would treat these issues region by region, first attending to the Western sphere and then to the West Asian and East Asian stories.

Order, Legitimacy, Justice and Revolution

In his doctoral thesis, Kissinger defines the concept of “Legitimacy”. According to Kissinger legitimacy is an international agreement about the nature of workable arrangements in a global situation. It should not be confused with justice. It sets the limits of permissible actions and a balance of power. It enforces a restraint on the global politics and diplomacy. A regime that does not accepts the ‘legitimate order’ of the times, is “revolutionary”. Also, an international order that is not accepted by all the major powers is revolutionary, and it creates international instability, until a new order aggregable to all is established.

Throughout the book, Kissinger demonstrates the mechanism of legitimacy, order, instability and the movement leading to the establishment of a new ‘balance of power’.

We shall examine this concept in the context of discrete historical examples as illustrated in the book. To maintain continuity and coherence additional material will be added as deemed necessary.

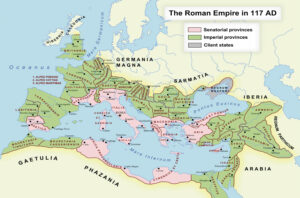

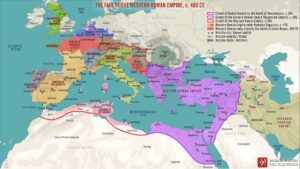

Europe

Europe after the fall of Western Roman Empire in AD 476 was a fragmented entity, particularly in the central European area. The Roman Empire fell because of multiple factors, including overstretching of administrative logistic, weak rulers, and uprising and invasion by various tribes from its neighboring territories. The fall was well anticipated by its earlier rules, and the original Roman Empire was divided into 4 territories by Emperor Diocletian in AD 293 for administrative ease. This soon led to conflicts between the rulers, and Emperor Constantine Licinius, son of one of the four Emperors consolidated it into one Empire. Constantine established a new capital, Constantinople, in the region of the present-day Istanbul. He converts to Christianity and soon the Roman Empire become a Christian Empire. After Constantine’s death, the Empire would be divided on dynastic line (to son’s of the Emperor) into Eastern Roman Empire based in Constantinople and Western Roman Empire based in Rome ( until AD 286), Milan ( 286-402) and Ravenna (402-476). This division become permanent as Western Roman Empire became politically, economically and culturally weaker than its Eastern counterpart due to a multitude of reasons.

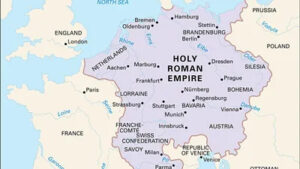

The Holy Roman Empire

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the territory was occupied by various Germanic tribes. The dominant among them was the Frankish tribe (known as Franks) occupying the Rhine region in the territory of modern Netherlands, Western Germany and Belgium). They had been allies and adversaries of the Roman Empire. Under the latter’s influence they were variably Christianized. After the fall of the Roman Empire, a Frankish king, Clovis I unified the Frankish tribes. He converted to Christianity in AD. 496. He established the Merovinigian dynasty (after his ancestor Merovech). The Frankish Kingdom was quite decentalised, ruling through local counts and dukes. By 7th century, the Frankish King lost much power and administrators of the palace ( mayors) usurped the real power. One such mayors of the court, Charles Martel, established the Carolingan dynasty. Martel’s great grandson emerged as a major conqueror who not only unified the warring tribes, but also brought Christianity to the recalcitrant tribes like the Saxons. His exploits included destruction of Saxon villages, destruction of their sacred sites, massacres of Saxon elites, forced submission and baptisms of Saxon chieftains and ultimate cultural annihilation of their beliefs and rituals.

Charlemagne’s work in Christianization of the German territories were recognized by Pope Leo III. He was anointed as the Emperor of the Romans, and his kingdom was named as the ‘Holy Roman Empire’. However, the so-called Holy Roman Empire did not have the administrative structure of the erstwhile Roman Empire. Rather it was a loose confederation of Germanic and Italian territories. It weakened further after Charlemagne’s death. By 15th century, the the ‘Empire’ was a confederation of over 300 semi-independent states including duchies, free cities, bishoprics ( bishoprics=a district under a bishop’s control) and even estates. The title of ‘Holy Roman Emperor’ eventually became a sort of ‘elected title’, elected by a select group of powerful princes in the ‘Empire’. The ‘election’ itself was not transparent. It was mostly influenced by bribes and competing lobbies involving dominant dynasties and the Pope. Essentially there was a ‘balance of power’ operating in securing the title of the Holy Roman Emperor. This arbitrariness of the empire and the emperor made French philosopher writer Francois-Marie Voltaire to quip that the Holy Roman Empire was “neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire.”

Thirty Years’ War

In 16th century a religious inflight ( what the church historians call as ‘schism’) would split Europe. A German priest named Martin Luther raised an open rebellion against the Church. One of his principal rallying point was against a practice known as ‘Indulgence’.

According to church’s doctrine the Church had accumulated a ‘treasury of merit’ accumulated based on the suffering Jesus Christ and his follower-martyrs (Like Saint Peter) bore in the early era of Christianity. This ‘virtue points’ church could choose to sell in return of atoning sins of layman. Here, Church was almost like a bank that took away sins for a payment. The sinner could pay the church to get himself free of sins. It was quite a transactional relationship between the Church and the layman who would sin in their course of life. Church had a list of sins according it theology based on Ten commandants and ever increasing volumes of interpretation around it.

The church would use the fund so generated to fund grand construction like the St Peter’s basilica in Rome. The Pope’s palaces in Rome itself is a testimony of the opulence of the popes of medieval times. Pope’s commissioned highly regarded artists like Michelangelo, Raphel and Da Vinci to erect and decorate Church’s buildings.

Many princes in the German speaking regions would side with Martin Luther and become Protestants kingdoms. The Protestants kingdoms would fight against Catholic Kingdoms. Catholic regimes would initiate persecution against suspected Protestant sympathiser in their reign. Protestants in-turn were rebel groups who want to make more and more converts to their side, firmly believing that Catholics were sinners who need ‘reformation’. This created tension in European states that many a times reached flash points.

A religious war would erupt between states that follow protestant ideology and those that maintain the primacy of Roman Catholic church. This is known as the Thirty Years War. It would ravage the Central European states decimating its population by as much as 25% in the course of time.

Cardinal Richelieu and the Doctrine of ‘Raison d’etat’

While the original trigger for the war was religious, there were many states in the Europe who used the war to increase their material gains and power. France, a catholic state was one of them. France used the opportunity of the war to delimit the influence of its rival catholic empire, the Austrian Habsburg empire. It supported the protestant states in the region of the present-day Germany to weaken the Habsburg empire.

The principal architect of this policy was, strangely, a cardinal known as Cardinal Richelieu. Richelieu was the chief minister to King Louis XII of France. Highly intelligent and scheming, he ascended to power in 1624. He was instrumental in curtailing the power of nobility by dismantling their private armies and strengthening the administrative control of the Royal house. Kissinger states the it was Richelieu who invented the idea that the state is an ‘abstract and permanent entity existing in its own right’. As per Kissinger Richelieu thought that states requirement is not determined by the ruler’s personality, family interests or the demands of religion. Rather its guide is the ‘national interest’. This is what is later known as the ‘raison d’etat’, the reason of the state. It states that the interest of the state takes precedence over everything else- it justifies morally indefensible actions done for the interests of the state. This includes sacrificing individual rights, moral codes and religious universal ideas for the interests of the state. Richelieu support for the coalition of Protestant states like Sweden, Spain and Netherlands to weaken France’s political rival Habsburg Empire in the Thirty Years war is cited as the prime example of this doctrine. In justifying this action Richelieu said: “If the Protestant coalition is ruined, the brunt of the power of the House of Austria will fall on France.” Therefore, in supporting the minor states in the Central Europe, Richelieu was checking the rise of Austria, notwithstanding the fact that the Thirty Years War was essentially a war of religious dogma, fought between Catholic state and Protestant powers.

Kissinger concludes his comment on Richelieu by making three conclusions: One, the indispensable element of a successful foreign policy is a long-term strategic concept based on the careful analysis of all relevant factors; Two, the statesman must analyse the conflicting pressures into a coherent and purposeful direction; Three, he must act at the ‘outer edge’ of the possible.

The Treaty of Westphalia

By 1640s the misery of war has caused incalculable damages in the form of death, disease and famines, and no clear winner were emerging. France and Sweden mooted negotiations to end the war. Initially the Holy Roman Empire was opposed to negotiation, but later it agreed for a treaty. In 1648, representative of multiple warring countries met in the German region of Westphalia to reach at a multilateral treaty. They agreed for solution that would form the basis of most of the arrangements of the diplomatic order in the world until now.

The treaty recognized the autonomy of individual states to govern themselves without external influence. It recognized the religion of the state as the stated religion of the heads of the state. It established the modern practice of permanent institution of diplomatic missions in various nations in state capitals. It reinforced the concept of non-hostility towards diplomats. It recognized the sovereignty of about 300 German, mainly protestant principalities, weakening the hold of the Holy Roman Emperor. It recognized protestant denominations of Lutheranism and Calvinism as legal, which rulers can choose for themselves without interference by the Pope or the Holy Roman Empire.

Balance of Power

But the political consequence unseen in the treaties was the diplomatic and strategic concept of ‘balance of power’. It made unwritten rule in the European diplomatic and strategic thought that if one power become too much powerful, other powers would form a strategic alliance to limit the power of the former. This played out multiple times in the future, leading to multiple ‘breakout’ wars, and realignment of coalitions. Kissinger states this as a form of ‘ideological neutrality and adjustment to evolving circumstances’. He quotes British Prime Minister and foreign policy expert Lord Palmerston to buttress the approach: “We have no external allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.”

According to Kissinger this ‘balance of power’ arrangement that emerged since the Peace of Westphalia prevented major catastrophic wars between European powers for some period. Until the World War I, Britain acted as the arbitrator that maintained the balance. It would switch sides in the European alliance when one of the continental states appear to grow bigger and exert disproportionate influence to tilt the balance in its favour. The minor wars that happened in this period were skirmishes that emerge when the balance tilt in one or another side. When the French king Lousi XIV tried to wield too much influence, Britian sided with Holland, Austria, Spain, Prussia and Denmark to maintain order. When the German unifier, Fredrick emerged to threaten the balance, his allies against the France switched sides to contain Germany.

The political consequence of the Westphalian order was that the Holy Roman Empire became meaningless. There is no longer a single Christian overlord. Every ruler claimed that they have divine authority to rule. Rulers mutually agreed that there are other rulers who have similar authority in other countries. Therefore, war was fought for limited material objectives like land. Holy wars were no longer meaningful.

French Revolution

But soon the relative peace of the Westphalia would be unsettled by another massive event- the French Revolution. French revolution was preceded by few cultural and political events. The emergence of scientific revolution in Europe, a set of philosophies and political thought tied to what is known as the ‘Age of the Enlightenment’, and the political events that unfolded in the Americas with the establishment of the American state and the declaration of American Independence.

The Age of Enlightenment followed the explosion of scientific knowledge in the 17th century. It was in a way application of the tools of reason into the field of humanities. There was newfound enthusiasm in the power of empiricism and rational thinking. The invention of printing press and spread of literacy following the protestant movement provided the context for the Age. Newspapers, pamphlets and encyclopedia that document the invention and discoveries provided access to information for the new age philosophers to rethink the world.

Kissinger quotes Denis Deberot (1713-1784), the chief editor of a monumental work that sought to gather and compile all human knowledge of the time, the 28 volume, Encyclopedie: “Reason would confront falsehoods with solid principles to serve as the foundation for diametrically opposed truths”, by which “we shall be able to throw down the edifice of mud and scatter the idle heap of dust”, putting “men on the right path”. The Encyclopedie, subtitled as ‘A Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts’, had about 140 contributors, 70,000 articles and 2500 illustrations. Eleven volumes of the project were devoted to illustrations. The contributors of the project include figures who would later connected to the Revolution like Voltaire, Rousseau and Montesquieu. Encyclopedie was banned multiple times by the French monarchy and the Catholic Church. It was instrumental in the spread of knowledge beyond the aristocracy and the clergy.

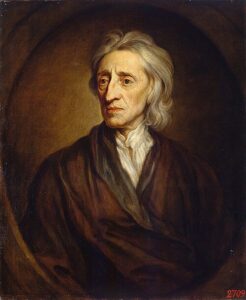

Application of rational analysis used in the Sciences to humanities lead to critique of the nature of institutions of the time. Ideas like Social Contract replaced the fable of divine rights of monarchs. The British Philosopher John Locke developed concept of ‘natural rights’ of human beings. Francois Voltaire critiqued the Church and Monarchy and elucidated concepts of civil liberties and free speech.

Charles Montesquieu, a French lawyer and political philosopher developed the concept of separation of powers of the states into legislative, executive and judicial, providing the foundation of the modern concept of check and balances in the functioning of the government. French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau advocated the concept of ‘popular sovereignty’, that the power to rule must come from the ‘general will’, not as a divine right of kings and the aristocracy. He maintained that the legitimate political authority is based on the ‘social contract’ freely entered by all citizens.

Kissinger opines that French Revolution’s ideology treated all monarches as their enemies, as they would not give up power without resisting. Therefore, the movement to prevail had to become a crusading international movement imposing its principles globally. Thus, the Westphalian limits of ‘sovereignty’ was not applicable to French revolutionaries. They considered permanent revolution that knew only total victory or defeat. In 1792, the French National Assembly made a commitment to extend French military support to popular revolution anywhere. It stated: “The French nation declares that it will treat as enemies the people who, refusing liberty and equality, may wish to preserve, recall or treat with the princes and the privileged castes.”

To prevent restoration of the old order the revolutionaries unleased a terror that killed thousands of former ruling classes and all those suspected of domestic opposition.

Kissinger notes that similar ‘cleansing’ happened later in Russia in 1930s and in China in 1960s. In France these purges went out of control, and finally some order had to established. Then came the French military leader who had made massive gains in campaigns elsewhere – Napoleon Bonaparte.

End of the Revolution and the Napoleonic Campaign

In 1799, after a military coup and following the tradition of the Roman Republic, three consul were made to assist the republic. Napoleon named himself the ‘First Consul’ and held all the power. Later, in 1804 he would anoint himself as the Emperor of France in the presence of Pope Pius VII, a symbolic act providing him legitimacy. However, unlike Charlemagne of the Holy Roman Empire, Napoleon took the crown from the Pope’s hand to crown himself, suggesting that he himself has gained the crown.

Napoleon saw himself as a ruler of the ‘Age of Enlightenment’. He rationalized the French system of administration. This system of administration, until then ad hoc according to the whims of the lord feudal lords, became knowns as the Napoleonic Code. Thereafter, Napoleon would ride a roller coast ride through the Europe, winning 46 battles of the total 60 major battles he was engaged in. At its peak he would conquer nearly all western, central and southern Europe, enacting his administrative reforms in all these territories. The Napoleonic Codes would become the standard of civil rules in these countries ever since. The Codes abolished the privileges of the feudal class, separated church from civil law, made ‘rule of law’ a standard of governance and provided clearly written formulations that protected private property and inheritance rights.

Napoleon wanted to contain the then Naval super-power Britain. France did not have a Navy powerful enough to take on Britain on the seas. Therefore, he adapted a strategy of continental blockade of Britain, using his influence in the Europe to restrict British trade with the other European countries. This was largely successful with the countries under his direct influence like the central European countries, Russia under Tsar Alexander I used to defy the blockade and trade with Britain. Napoleone thought that this if unchecked this would undermine his authority, and soon other European countries under his suzerainty would follow suit.

Napoleon’s campaign of Russia in 1812 would be disastrous. His army would be overstretched and as the winter set in his army could not provide the logistics necessary for a prolonged war. Russia, in its tactics, would adapt its famed scorch earth strategy, destroying its land before retreating. Russia’s strategy of planned retreat would not stop even when Napoleon’s army reached Moscow. It would burn down — of Moscow as Napolean advanced to its capital. Finally, unable to sustain in the face of cold, death, and disease Napoleon would retreat. The army that marched into Russia with 600,000 men would return as a much-beaten group of 100,000.

Napolean’s failure to subdue Russia would encourage his European advisories to gang up. Soon, an alliance of Russia, Prussia, Austria and Sweden will defeat Napoleon in the famous Battle of Nations in Leipzig in 1813.

The coalition army would march to Paris, and in 1814 Napoleon would abdicate as the Emperor of France. He will be exiled to the island of Elba. Although Napoleon made a dramatic comeback in 1815, he would be defeated decisively in the Battle of Waterloo. He will be exiled to the distant island of St Helen in the Atlantic Ocean, never to think of a comeback.

Congress of Vienna and the Concert of Europe

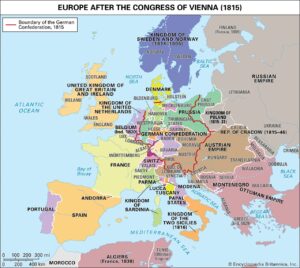

After the defeat of Napoleon Europe’s boundaries will be redrawn with three expressed interests: One, reinstating the status quo that Napoleon had dismantled; Two, to provide a counterweight to the expansionist interest of France; Three, prevent revolutionary uprising similar to that of French revolution arising elsewhere in Europe

The diplomats of Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria and France met at Vienna in 1814-15 to arrive at a solution. One of the important decisions was to consolidate the central Europe to confederation of 37 states. This was so that there is a sizable ‘mass’ of nations that could resist France adventures in the future. Russia gained most of Poland and Finland. Austria got northern Italy, and Britain gained overseas territories like Ceylon and Malta. France returned to its 1792 border, and the Bourbon monarchy was restored. To protect the arrangement an alliance, the Quadruple alliance of Britain, Prussia, Russia and Austria was formed. Russia’s Czar proposed a Holy Alliance that provided for protecting the domestic status quo in Europe. The right to intervention was exercised only in concert, as Austria and Prussia had a veto over Czar’s decisions. There was a mechanism for a periodic diplomatic conference of the head of governments to deal with emerging crises. Kissinger states that this functioned like the precursor of the United States Security Council.

The security arrangement would quash uprising in various European countries in the next 60 years. This include liberal revolt in Spain demanding constitution in 1812, constitutional revolt against Italian ruler Ferdinand I in 1820, Nationalist uprising against the Pope in 1830, and Revolutions of 1848 in Austria, Prussia and Russia. These revolts were all crushed by the alliance partners. About 100,000 people would die in all these revolts. Not all revolts were suppressed. The Belgium revolt against the Dutch rule was taken kindly by Britain, who saw it an opportunity to get the port of Antwerp free of rival influences. Britan was successful in supporting Belgium in gaining independence. Belgium was declared as a nation that would remain neutral in all subsequent conflicts. This was the first instance in which a nation is declared neutral by all major powers. This undertaking made it an obligation for the alliance powers to resist violations of Belgian neutrality.

Emergence of Nationalism

Napoleon’s conquest of Europe precipitated a new formulation of political identity. There was animosity against occupation forces, and development of a political consciousness based on linguistic and cultural identities. Two important developments were the German and Italian unification. German confederation of states made as a security against future French dominance in central Europe saw the seed for nationalist aspiration in German states. Prussia would utilize the unity aided by the confederation to accelerate German Empire building in the subsequent years. Napoleon had dismantled multiple regencies in the region of Italy. While the congress of Vienna reestablished the older regimes, nationalist aspiration would be kindled on the ideological front which would lead to its eventual unification by the end of 19th century.

The work of German writer Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803) who argued that each ‘volk’ (people) has a unique ‘Volksgeist’ (‘spirit of the people’) shaped by its language, tradition and customs was revisited and found echo in many later thinkers. Here the idea of ‘Enlightened pluralism’ as constituted by multiethnic countries were rejected, and development of nations on the grounds of common language and customs gained ground. This included thinkers like Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814) and Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) who propounded for German Nationalism under a common medium of language.

The development of German Nationalism favoured the emergent state of Prussia against the multiethnic Austria. Although initially deferential to the Austria as the holder of the Holy Roman Empire, Prussia soon became assertive and confrontational.

In 1853, Crimean war broke out between Russia and the Ottoman Empire when Russia invaded Moldavia. This was partially in retaliation to Ottoman’s refusal to give Russia rights over Christian holy sites in the Ottoman-controlled Jerusalem. The other European powers of Britian and France saw Russia’s action as an aggressive maneuverer to tilt the balance of power, and supported Ottomans against Russia. Austria would refrain from helping Russia. This would ultimately end the alliance of European concert that had emerged after the Congress of Vienna.

Soon, France under Napoleon’s nephew Napoleon III ( Louis Napoleon Bonaparte) would have a secret alliance with the Italian region under Austria possession, Sardinia-Piedmont, to provoke Austria and incite war. Austria falls into the trap, which ultimately lead to Italian unification. Repaying in kind, Russia will not come to aid of Austria. The understanding of the Congress of Vienna was thus almost dismantled.

Germany as a Great Power

Prussia, a small kingdom in the present day Poland emerged by the late 18th century as nation that could lead German speaking states after the dissolution of the Holy German Empire through a series of wars, military modernization and realpolitik maneuvering to be main state in the central Europe representing German speaking population. The country was marshaled by its efficient king Frederick II and its exceptional chancellor Otto von Bismarck mainly through the development of a militarist state with a focus of on brute victory. Fredrick followed the principle of ‘raison d’etat’ enunciated by Cardinal Richelieu. Kissinger states that Fredrick was a ‘benevolent despot’ whose rule was legitimized by its effectiveness, not ideology. In its conquest to expand its territory to the Austrian region of Silessia, he sought no moral justification, but ‘the superiority of his troops, the promptitude with which they can act’ was the sole justification needed.

Otto von Bismarck who ruled from 1862 to 1890 believed that power should not be restrained by any superior principle. For him the only ‘healthy basis of policy for a great power is egotism. Gratitude and confidence will not bring a single man into the field on our side; only fear will do that—’

A superb diplomat, Bismarck would stick conflicting alliances with the neighboring powers to keep them in check. He would have Austria and Russia in Three Emperors’ League (1873) to unite conservative monarchies, Dual Alliance ( 1879) with Austria-Hungry as defense against Russia, Reinsurance Treaty (1887) with Russia to ensure Russia’s neutrality in case of war with Austria and Mediterranean Agreements (1887) with the Britain, Austria-Hungary and Italy to prevent Russia naval expansion in the Mediterranean region. Few of these agreements were made secret ( example- Reinsurance Treaty with Russia and Mediterranean Agreements, while few had secret military clauses ( eg Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Italy to isolate France).

These cynical alliances would soon backfire when Bismarck was dismissed by Wilhelm II as the Chancellor. It would lead to lapse of Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1890, inciting Russia to make alliance with France, something which Bismarck wanted to avoid.

World War I and the Abolition of German Empire

The Kaiser, Wilhelm II, would thereafter embark on policy of military expansion focusing on colonial aspiration and a naval arms race with Britain. The disruption of Germany’s secret pact with Russia would provoke a Franco-Russian Alliance in 1894. Germany’s aggressive posturing would lead to a Anglo-Russian Alliance ultimately leading a Triple Entente among France, Russia and Britain. In June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria will be assassinated by Serbian separatist in Sarajevo. Germany would give a diplomatic assurance to Austria to be stern with Serbia. Emboldened Austria would give a ultimatum to Serbia involving terms impinging on Serbian sovereignty. Although Serbia complied with most of the demands, Austria declares war on Serbia. Russia would mobilize army in Serbia’s defense. Germany would jump in and declare war on Russia and France, invading France preemptively based on preplanned military doctrine ( Schlieffen plan), sweeping through neutral Belgium. Violation of Belgium’s neutrality previously guaranteed by Britian would provoke Britain to declare war on Germany. Within a period of a week’s time a continental war that would soon engulf as the first world war would ensue.

World War I would lead to the abolition of the German monarchy. Kaiser Wilhelm would be forced to abdicate and retire to Netherlands. Germany would cede Western Prussia to Poland. It would be asked to pay huge reparations, leading to hyperinflation in Germany. All German colonies would be redistributed among the Allied powers.

During the rule of Bismarck there was development popular socialist movement in Germany. Bismarck was anti-socialist. He countered it with development of a health insurance and pension scheme for workers, the first of its kind in Europe. At the political side he was in favour of suppressing the movement, considering it as anti-conservative and anti-monarch. The Kaiser Wilhelm, on the other hand, was for coopting the movement for nationalist purpose. One of the reasons for Bismarck’s dismissal was related to handling the socialist and workers movement.

As the World War I progressed, the socialist movement took steam. The Social Democratic Party (SDP) of Germany was founded in 1875. Bismarck was a staunch opponent of socialist movement. He clamped Anti-socialist laws in 1878, outlawing meetings, organization and press coverage. He initiated health insurance and old age pensions in Germany to counter popularity of socialists. With the world war, there was division in the socialist movement. SPD supported war efforts, while moderate and radical socialists were antiwar. Radical Marxist revolutionary faction led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Friedrich Liebknecht sought proletariat revolution. In 1918 there was a mass uprising and revolts known as German November Revolution. It lead to abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the end of the German monarchy. A republic led by SPD leader Friedrich Ebert was formed, known as the Weimer Republic. The allied armistice with Germany was conducted with the civilian government. Abdication of the Kaiser and the formation of civilian government was one of the demand the US President Woodrow Wilson kept from the Allied side as a precondition of the truce talk. In 1919 the radical communists led a revolt known as Spartacist Uprising. The SPD movement crushed this revolt. Freikorps ( ‘Free Corps’ )a paramilitary alliance of ex-military men and monarchists were involved in the violent suppression of the Spartacist. The leaders of the Spartacists, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were executed. The Allied would sign the peace treaty, the Treaty of Versailles with the Weimer Republic. It was a sort of forced treaty as Germany was not involved in negotiation and the Germany of threaten of literary occupation if they did not sign the treaty. The chief clause of contention was Article 231, making Germany solely responsible for the war. Germany would lose it 13% of its land and 10% of its population to France, Belgium, Poland and Denmark. Its overseas territories would be seized by the Allied, and its military would be restricted to 100,000 soldiers and Western region of Germany would be demilitarized as a buffer zone. Part of the Prussia would be given to Poland and the German French speaking industrial hub, Alsace-Lorraine would be given to France. Germany would be made to pay $ 33 billion in reparation as the sole surviving aggressor who led to the WWI.

German as a Troubled Republic

Germany’s transition to a republic was marred by violent agitations from both sides of the political divide. The right-wing monarchists were a dominant force. They resented the terms of Treaty of Versailles and blamed the civil government for capitulation. The right wing militia of Freikorps constituted by ex-military men and monarchists engaged in violent conflict with the Left wing workers’ parties. The social democrat German government, in turn, would covertly use Freikorps to suppress radical left movement. The Freikorps would be funded by the disenfranchised landlords, capitalists and secretly by the government as well.

There would be about 350 targeted assassination conducted by the Freikorps from 1912 to 1923. This includes German foreign minister Walter Rathenau and former finance minister Mathias Erzberger. They were targeted for being party to the negotiation of Treaty of Versailles. In 1920, irked by the enactment of the Treaty clause limiting the number of miltary to 100,000, the monarchists generals would march to Berlin and seize power. The coup leaders, a Prussian land lord named Wolfgang Kapp and German general named Walter von Luttwitz declared that they would reinstate the monarchy. The German government would flee to Stuttgart. The German military would refuse to defend the government, saying, ‘Reichswehr does not fire on Reichswehr’ ( ‘the imperial defense does not fire on itself’). But the coup did not last as there were nationwide strike led by the left-wing parties, forcing the coup leader to capitulate in a matter of 4 days. The coup leaders would flee the country, but the lenient judicial system in Germany at that time would allow the coup leaders unpunished.

The workers uprising in the industrial base in Ruhr valley would, however, continue even after the coup was terminated and the government reestablished. The workers were angry at the inability of the government to secure democracy. There were demands of in a section of strikers in establishing workers democratic council, like the Soviets. The Social Democrat in the government interpreted it as attempts to overthrow the government. They used the military and the Freikorps to violently suppress the uprising in Ruhr. The military engaged in indiscriminate violence, and about 1000 workers were executed without a trial. It appeared that the SPD government used the very military and Freikorp militia that tried to overthrow the government to suppress the workers who rouse in support of the government. This would further increase the divide between the Social Democrat government and the workers’ parties. There would be steady radicalization of the society between the rightist and leftist groups both opposing the government.

Monarchists would assassinate German finance minister, Mathias Erzberger and German Foreign Minister Walter Rathenau for having been involved in the negotiation for signing the Treaty of Versailles. They believed that Treaty was a ‘stab in the back’ by Jews and socialists to the German honor. This was an outcome of non-involvement of military generals in the armistice of WWI. While the military leaders avoided involving in the negotiations to preserve their honor, it became a pretext for the propaganda that German army was not defeated in the WWI. This interpretation would become a cornerstone in the Allied forces’ behavior in the subsequent WWII, where the latter ensured complete German surrender before ending the war.

German Hyperinflation and Dawes Plan

During the WWI, Germany had resorted to printing money without raising taxes. After the war, Germany was made to commit massive reparation to the Allied. The total reparation committed in the Treaty of Versailles was 132 billon gold mark (Germany currency Mark pegged to gold). Post-WWI Germany could hardly manage this amount. In l921-1923, Germany experience one of the worst hyperinflation in the history. The prices of the commodities increased by 50% every month. The annualized inflation was more than 13000%. Currency lost its value, and people started to resort to barter system.

With Germany delaying reparation payment, France and Belgium would invade the Ruhr to take over coal and steel production from the region. However, there was massive workers protest and non-cooperation. Germany printed more money to pay for workers who were striking. This exacerbated the economic crisis, and Germany economy collapsed by late 1923. There was widespread resentment against the French act of invasion of a demilitarized zone of Ruhr. Germans considered it as a violation of its sovereignty and a major humiliation.

With the French-Belgium invasion and the German hyperinflation, the Allied under the leadership of the United States would constitute a committee in the chairmanship of American finance expert Charles Dawes. The Dawes committee would restructure the reparation payment and would initiate measures in stabilizing the German currency. It would provide $ 200 million of loan to the Germany to provide help recovery of German economy. The reparation would be staggered, and France would withdraw from the Ruhr region.

Following the Dawes’ measures the German Republic stabilized by late 1920, to the extend it was called the ‘Golden Twenties’. Germany was slowly integrated to the global political and economic system. However, the Plan made Germany dependent on financial system. In 1929, when the Great Depression struck the United States, US investors started to withdrew capital, and by domino effect the German economic system started to fail. About 30% of the workforce became unemployed with the Great Depression. Businesses were shut down and industrial output halved. The disturbances made the Nazi party popular. Its blame-shifting tactics and the promise of a muscular foreign policy made it increase its sphere of influence. In 1932, the Nazi party became the largest party in the German parliament. This was a striking rise from a minority party with 6.5% votes and 32 seats in 1924 to a majority of 37% votes and 608 seats.

Fall of the Republic and the Rise of the Nazis

Monarchists thought that coopating Nazi party would help to reestablish the old order. The German President, Paul von Hindenburg, a World War I general, invited Adolf Hilter to head the government in January 1933. As Hitler did not have majority to rule, the conservatists thought that he can be ‘controlled’ by the strength of their votes. However, Hitler soon overrun Hindenburg and the conservatists to take over all centers of power.

In February 1933 there was fire in the German parliament, Reichstag. The government, implicated a Dutch communist, Marinus van der Lubbe, in the incident. Although Lubbe said that he acted alone, the government incriminated the whole communist party and arrested all the communist party parliamentarians. With parliament downsized, Hitler got Hindenburg to pass a decree called the ‘Enabling Act’ that gave the Chancellor powers to make laws without the approval of the parliament or the president. It effectively neutralized the parliament, giving legislative power to the executive. With the act Hitler and his cabinet could enact law even if they violated the constitution, removing the checks and balances that is standard in a liberal democracy. Soon Nazi Party banned or dissolved all opposing parties, establishing a totalitarian rule.

In effect the Nazi party came to power through democratic route, but became dictatorial single party by deft use of tact and power. During the Weimar Republic, from 1919 to 1932, there were 18 cabinets of various coalitions. The Republic was modelled on representational democracy of Switzerland and Belgium, where party seats in the parliament was proportional to the vote share it had. Therefore, the parliament had multiple parties, and government was formed only by means of coalition of parties with dissimilar ideologies. This led to conflicts and short-lasting governments. The principal conflicts emerged around the willingness of continuing to give the reparation based on the treaty of Versailles. Those governments who tried to comply with the Treaty were considered ‘anti-national’. Coupled with the chronic issues of opposition to Treaty of Versailles, were the issues of hyperinflation and unemployment, making an impression that the traditional political parties are indeed responsible for the plight of Germany. Thus, when the opposition parties were banned, majority of Germans thought it desirable and did not vouch for the principles of democracy. Indeed, the principles of democracy was not well-rooted in Germany as in Switzerland. The society was hierarchical and following the dictatorial culture of the just deposed monarchy.

The Nazi government engaged in huge infrastructure projects and clandestine miltary restoration via deficit spending, by printing money and issuing promissory notes like Mefo bills ( Metullurical Research Company bills). The German Autobahn and People’s Car project Volkswagen was built during the era. These development activities led to reduction in unemployment and an ‘apparent’ economic recovery, although currency reserve was rapidly declining. Germany went into war in 1939. Once the WW2 broke out Germany started to sustain itself by looting the gold reserves of the conquered nations.

In March 1933, Germany left the League of Nations and the Geneva Disarmament Conference. In March 1935 it announced conscription for its military and in March 1936 sent troops into the demilitarized zone of Rhineland effectively renouncing all the clauses of the Treaty of Versailles. The Allied Forces, although witness to Hitler’s belligerence in slowly dismantling the Treaty, were not ready for another war. They tolerated German advances until it invaded Poland in September 1, 1939. In September 3, 1939, Britain and France would declare war on Germany, setting off the Second World War.

World War II and the New World Order

World war II smoldered for 6 long years. Sixty million people would die. Six million Jews would die in Nazi concentration camps. The German invasion of the Soviet Union would cause 27 million deaths for Soviet Union.

United States would entered the war in Dec 1941. The Allied would land in Normandy, France in June 1944. Soviet army would enter Berlin in April 21, 1945. Hitler committed suicide 1 week later. The Allied forces would impose a condition of unconditional surrender after a thorough capitulation of the German army as a demonstration of total defeat of Germany. This was to ensure that Germany won’t recant a story of ‘stabbing in the back’ as had happened after WWI armistice.

The Postdam conference of July-August 1945 would divide Germany into zones of occupation. It would aim to complete demilitarization and denazification of Germany. Berlin would be divided among four victorious Allied Forces- USSR, USA, Britain and France. About 25% of territory held prewar would be given to Poland and northern part of East Prussia would be given to Soviet Union. About 10-12 million ethnic Germans would be expelled from the territories handed over to Poland to prevent future ethic conflicts.

The occupation zones of France, Britain and USA would be combined to create the Federal Republic of Germany, while the Soviet occupation zone would become the Democratic Republic of Germany.

Germany under Probation and the Emergence of European Union

Preventing Germany’s remilitarization would be the aim of the Allied in the initial year of the post-war. Germany would be in a ‘probation’ for many years following the war. The FDR would be administered by Konard Adenauer a Christian Democratic Union politician with a clear anti-Nazi, anti-communist, pro-Western credential. He would initiate a process of reconciliation that would end up with the development of Coal and Steel Community, an economic union between Germany and France that would set the stage for forming the European Union, transcending the traditional rivalries between the nation states of Germany and France that lead to centuries of catastrophic wars. The United States would provide a security umbrella that allowed this union to flourish without account of a strong military of their own.

Kissinger opines the arrangement of European Union as a hybrid, something between a state and a confederation, more like the Holy Roman Empire than the nation-states of the 19th century. In foreign policy it embraces universal ideas without ability to enforce it, depending heavily on the US for security and authority. Kissinger doubts about the direction it is taking as it is torn between the anxieties of influx of people of non-European origin.

Conclusion to the first episode (Europe)

Kissinger’s concept of balance of power and legitimacy through appropriate balancing of power did not establish peace in Europe beyond a short period of time. Balance of power induced-legitimacy operated for short stretches of time, but was ultimately overturned by operators like Napoleon, Fredricks II, Wilhelm II and Hitler. Here, while Napoleonic agenda can be considered revolutionary, the agenda of German operators were to establish their own Empires based on their world view of an expansionist doctrines. These operators lead to catastrophic wars, requiring forces outside the European sphere to reestablish order. Each of the ‘operators’ left behind a legacy that changed world views: Napolean spread the values of European Enlightenment and enshrined a civil code in feudalist Europe, Fredricks II and Wilhelm II built Germany as a disciplined nation-state from the fragmented Germanic kingdoms, Hitler created a scare of demonic nation-states, causing a watershed moment in the world that started to abhor totalitarianism and racial hatred.

United States who was maintaining an isolationist approach during most of its initial tenure due to the American skepticism of the European conception of order ( the balance of power doctrine), had to intervene both in WWI and WWII to get the conflagration back to equilibrium. After the WW2, however, the United States tend to shed its isolationist approach, and emerged as the real master who shepherded the battle-worn European out through their cynical world of power politics. But in this process, the United States would partake the cynicism which apparently detested until then.

We would see later that the Europe’s descent to the Nazi scare through the means of democracy would create a fire in Holocaust survivors like Henry Kissinger to disregard the outcome of democracy and exercise unmindful power in stamping out Anti-Americanism from its spheres of influence. From a neutral, external, point-of-view we would see Kissinger and the American approach under his tutelage being branded as monasteries worth war-crime like treatment. We would see this tension in diplomacy and ‘world-ordering’ playing out in politics and world views in the 20th and 21st century conception of the world.

Note

*Until the end of the WW2, racism was a standard framework applied in the global politics. In the United States, for example, racism was a method uniformly adapted in civil spaces. Madison grant, a respected conservationist and the proposer of the ‘Nordic Race’ theory, a popular theory vogue in his times, was an advisor to the US president Theodore Roosevelt. Hitler’s application of racism to its practical limits would disrepute racism as a theory.

Hits: 346